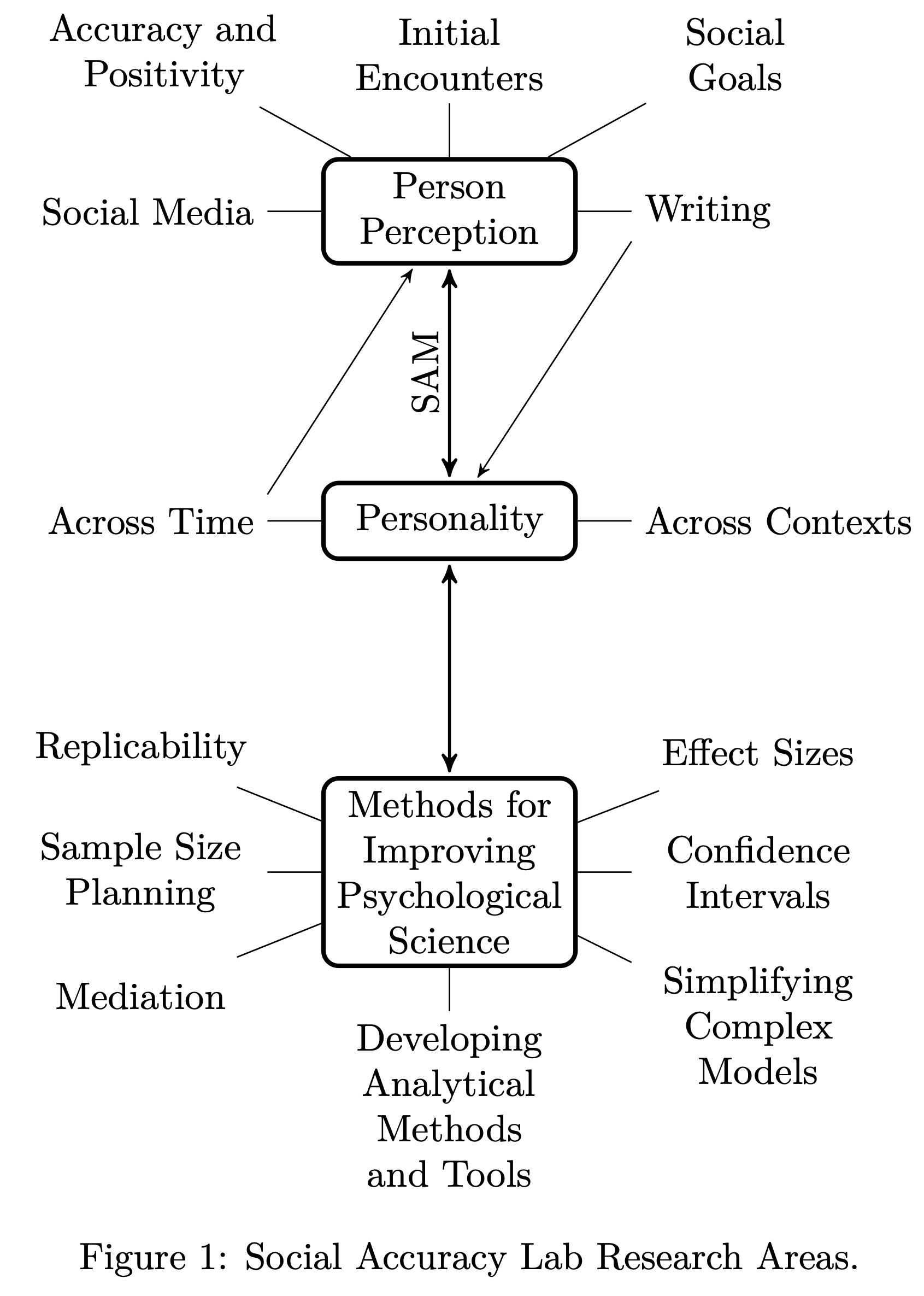

Research Areas

Research in SAL falls into 3 broad categories. First are questions about accuracy and bias in person perception using the Social Accuracy Model (SAM). For instance, when, why, and how are first impressions of others more or less accurate? Are some people more likeable than others and what are the consequences of likeability? Second, what is the nature and structure of personality? How can we better assess basic personality traits and dimensions? How does personality manifest over time? Finally, we are interested in developing, improving, and disseminating better quantitative tools for substantive researchers to improve the practice of psychological science.

The Good Target

One of the primary research questions we have been exploring is who is more accurately perceived and why. The social accuracy model is the only analytical framework that allows direct estimation of individual differences in the good target (expressive accuracy). Across all of our studies we have documented substantial individual differences in expressive accuracy and provided empirical evidence for the utility of SAM. Moreover, we have documented robust links between well-being and being accurately perceived which emerge across a range of social contexts (see Human & Biesanz, 2013, for a review). Human & Biesanz (2011) demonstrated that this relationship is consistent with judgability and inconsistent with adjustment being associated with enhanced self-knowledge. To explain why this relationship emerges, we combined a large round-robin first impressions study with a two-week experience sampling study and found that well-adjusted individuals tend to behave more in line with their stable personality traits in both these settings (Human et al., 2019). This is consistent with personality-behavior congruence, which is higher in well-adjusted individuals, allowing perceivers to gain a clearer understanding of their interaction partner after just several minutes of interaction. More recently, Wallace & Biesanz (2021) demonstrated that the good target is consistent across contexts (in person interactions and written essays) as well as across domains (broad personality traits and motivations). Similarly, Human et al. (2021) demonstrated that the good target is consistent across both in person interactions as well as more accurately perceived through their Facebook profiles.

The existence of strong individual differences in expressive accuracy also accounts for the difficulty historically in determining and assessing the good judge — someone high in perceptive accuracy. Using 4 large samples collected over a decade in my lab, Rogers & Biesanz (2019) demonstrated that the ability to assess the good judge of personality requires the presence of the good target. That is, some individuals are indeed higher in perceptive accuracy than others, but these individual differences become more apparent only with good targets. Since some targets are much lower in expressive accuracy, individual differences in perceptive accuracy (the good judge) appear less pronounced than those of the good target, on average across large samples of essentially randomly selected participants. In short, the existence of strong individual differences in the good target strongly attenuates the assessment of the good judge and may help explain the historical difficulty in assessing the good judge.

Accuracy, Positivity, and Normativity

The initial development of the social accuracy model estimated two components — distinctive and normative accuracy. Distinctive accuracy is analogous to traditional correlational measures of accuracy, but averaged across the different items or traits that are assessed in the model (i.e., it represents an average effect). However, traditional correlational measures (e.g., the correlation between perceiver evaluations of extraversion from Facebook profiles with the target’s self-report of extraversion) remove and discard mean-level information. In contrast, SAM explicitly preserves and models this mean level information. Careful consideration of this mean-level information suggests that it is conceptually comprised of two highly correlated components — positivity and normative knowledge. Positivity refers to the social desirability of perceiver impressions. Normativity, as modeled in SAM, refers to the association between average person’s personality and the perceiver’s impressions, controlling for social desirability. Rogers & Biesanz (2015) and Wessels et al. (2020) both demonstrate that although the average person’s personality is highly socially desirable, normativity and positivity are separate and independent processes in person perception.

Across our published papers using SAM (e.g., Rogers & Biesanz, 2019; Wallace & Biesanz, 2021) we have documented substantial individual differences in the positivity of impressions for both perceivers and targets. For perceivers, this individual difference can be interpreted as a relatively pure perceptual bias — some people simply view others more or less positively. In contrast, individual differences in positivity associated with targets represents a measure of their likeability. Likeability as measured by SAM represents an implicit measure of the consensus in how positively a person is perceived by others. Wallace & Biesanz (2021) demonstrated strong correlations in likeability across domains and contexts. People who are likeable in person are also those who are likeable through their written work as well. Our current work, unpublished at the moment, uses a large random sample of N=600 essays from the NCDS birth cohort study in the UK and demonstrates that likeability is stable across the lifespan (age 11 to age 50) and that likeability at age 11 is strongly associated with education and social class at age 42, even when controlling for family social class and education. Our current research efforts are focused on (1) understanding why people differ in likeability and (2) the long-term consequences of likeability.

Quantitative Methods and Research

My current quantitative research is quite diverse with the unifying theme of focusing on topics that require additional attention — in other words, building better quantitative tools for common problems faced by applied researchers. Recent examples include (1) novel approaches to examining mediational models (Biesanz et al., 2010; Falk & Biesanz, 2015, 2016), (2) sample size planning based on effect size estimates (in progress), and (3) generating confidence intervals for standardized effect size estimates based on both fixed and random predictors (in progress). Currently I am in the process of developing and expanding a package for R fabs that will serve as a repository of my quantitative work and code for these various endeavours. fabs is currently available on github and will soon be submitted as a package on CRAN.